Correction dated 23.10.2025: Changes have been made to sections 7.8.5 and subsequent ones to clarify the understanding of dimensions and the processes associated with them. The interpretation and characteristics of black holes have been revised.

Annotation

This paper presents a theoretical model describing matter, fundamental interactions and the structure of the Universe on the basis of unified wave principles and the concept of fractality. The paper aims to overcome the fragmentation of modern physical theories by offering an alternative approach to explain the nature of mass, electric charge, gravitation and the origin of fundamental constants.

The model is based on the idea that elementary particles are stable standing waves formed in Euclidean space, considered as an energy-rich medium. Interactions between particles and formation of all fundamental forces are interpreted as a result of resonance processes in this medium. The existence of a longitudinal component of electromagnetic waves, which plays an important role in the structure of matter, is assumed.

The term “longitudinal wave” is used here in an extended sense: it is not a new type of wave, but a part of the process associated with the front and the finite “thickness” of the electromagnetic wave. In essence, this is the same field, only considered not separately but as an integral part of the wave itself. This view makes it possible to unify the description of the wave and the field and to propose a mechanism of quantization through the equal work of space in the formation of each half-wave.

A mathematical model has been developed that allows to derive the key parameters of the main stable elementary particles (neutrino, electron, neutron, proton), such as mass and characteristic wavelength, from the first principles of the model, based on the quantisation of standing wave knots and the fundamental speed of interaction (speed of light). A mechanism for the origin of the elementary electric charge as a characteristic of the geometrical work done by space in forming the half-wave of the particle is also proposed. The theoretically calculated values of masses and charge show good agreement with experimental data.

The model offers an explanation of the constancy of the speed of light and derives the Lorentz transformations as a consequence of the wave nature of matter and resonance interactions. Within the framework of the fractal structure of the Universe such phenomena as dark matter and dark energy are interpreted, and the scalability of matter properties is predicted (e.g., the correspondence between the parameters of the neutron and the Milky Way galaxy). Implications of the model for understanding quantum entanglement are discussed and testable predictions are offered, including the dependence of the half-life of the neutron on the density of surrounding matter.

The proposed approach does not deny the achievements of existing physics, but seeks to integrate them into a more general and intuitive picture of the world, where the fundamental properties of matter and laws of nature are a consequence of the unified wave dynamics of energy.

Keywords: wave model of matter, fractal Universe, resonance, standing waves, origin of mass and charge, fundamental constants, unified theory of interactions, longitudinal waves

1. Introduction

Contemporary fundamental physics, despite significant achievements in describing a wide array of phenomena, faces a number of conceptual challenges. Existing theories, such as quantum mechanics and general relativity, successfully describe reality at their respective scales; however, their complete unification into a single comprehensive system remains an unresolved task. The origin and precise values of fundamental physical constants, as well as the nature of such foundational concepts as mass, electric charge, and gravitation, continue to pose profound questions. Furthermore, the phenomena of dark matter and dark energy, which account for a significant portion of the Universe’s energy balance, indicate the incompleteness of our current understanding. There is also a lack of a universal approach capable of describing the structure of matter at all levels – from elementary particles to the cosmological scales of galaxies – based on a single principle.

Many modern models rely on complex, at times abstract, mathematical constructs, the physical meaning of which is not always evident. This complicates an intuitive grasp of the nature of observed phenomena and hinders the creation of a holistic worldview. The concepts of the ‘point particle’ and ‘wave function’ are effectively employed to describe experiments; however, the intrinsic nature of these ‘points’ and the mechanism underlying wave-like behaviour remain beyond direct observation and complete theoretical comprehension.

This work proposes an alternative approach, founded upon a wave model of matter and the principle of the fractal structure of the Universe. The key hypothesis is that matter at all levels consists of stable standing waves, forming within a unified energy-saturated medium (the physical vacuum). Interactions between these wave structures, encompassing all fundamental forces, are interpreted as manifestations of a universal mechanism – resonance. Observed ‘point particles’, in this context, are considered to be localised regions of these wave processes, whose internal structure may be concealed from us due to limitations imposed by the speed of our perception and the nature of interactions.

The primary objective of the present work is to develop and present a theoretical and mathematical model which, proceeding from these wave and fractal principles, is capable of:

- Describing the structure and properties of the principal stable elementary particles (neutrino, electron, neutron, proton).

- Proposing a mechanism for the origin of mass and electric charge as characteristics of wave structures.

- Providing an interpretation for fundamental physical constants.

- Explaining the nature of gravitation and other fundamental interactions via a unified resonant mechanism.

- Shedding light on phenomena such as quantum entanglement and the nature of the photon, as well as offering an explanation for the effects of dark matter and dark energy within the framework of fractal scaling.

The proposed approach does not seek to negate the achievements of contemporary physics but, on the contrary, aims to integrate them into a more general and physically intuitive conceptual system. Many established laws and models remain valid within their domains of applicability, whilst acquiring new meaning in the context of wave energy dynamics. This work is directed towards simplifying the understanding of the world’s structure, offering an intuitively clearer picture based on the universality of wave processes and resonant interactions, supported by mathematical calculations whose results are compared with experimental data.

Additional clarification. In the following discussion of the structure of matter, the term “longitudinal component of the electromagnetic wave” is used. This term does not imply the introduction of a new type of wave. It refers to an internal aspect of wave propagation — its front and finite thickness, which account for the redistribution of energy in space. Thus, the longitudinal component is regarded as an integral part of the wave itself rather than as a separate phenomenon.

2. Postulates

The following postulates serve as the foundation of the proposed theory of the wave model of matter and fractal structure of the Universe:

- The Primality of Energy and the Nature of Space:

- Energy is the fundamental basis of all physical objects, phenomena and interactions. All things are different forms of manifestation and structurisation of energy.

- Space is not a passive void, but is an active energy-rich medium, possessing structure and capable of supporting and transforming wave processes.

- Wave Nature of Matter and its Properties:

- Matter is fundamentally stable standing waves formed in an energy-rich environment.

- Four basic types of stable standing waves are assumed to exist, which correspond to the main stable elementary particles (neutrino, electron, neutron and proton).

- The fundamental properties of particles, such as mass, electric charge and spin, are derived characteristics determined by the geometry, dynamics and stability of their wave structures.

- The mass is determined by the amplitude of the longitudinal component of the standing wave and its half-wave structure.

- Mechanism of Interactions:

- All interactions between particles and objects are carried out through resonance — the coordinated exchange of energy between wave structures.

- The fundamental forces of nature (gravitational, electromagnetic, weak and strong) are different macroscopic manifestations of a single mechanism of resonance interactions in the energy medium.

- Principle of Harmonic Resonance and Frequency Scaling:

- Interaction and self-similarity between different fractal levels are ensured by resonance. The condition for this inter-scale resonance is not the equality of frequencies, but their harmonic coherence.

- Each fractal series (for instance, our world) is characterised by a base frequency (ν₀) at the zeroth level (n=0).

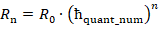

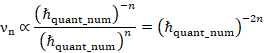

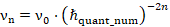

- When transitioning between fractal levels (n), this frequency scales according to a strict mathematical law (νₙ=ν₀⋅(ℏquant)²ⁿ), preserving the harmonic coherence of the entire system.

- It is precisely this harmonic connection, rather than an equality of frequencies, that is the condition for inter-scale resonance and determines the dynamic characteristics (including the limiting interaction speed Cₙ) at each level.

- The Geometry of Space and the Nature of Time:

- Space at a fundamental level is Euclidean.

- Changes in energy (its distribution and density) affect the formation and properties of wave formations (matter) in this space, but do not lead to curvature of Euclidean space itself.

- Time is not an independent fundamental entity, but a manifestation of the sequence of changes of energy states and wave configurations in space.

- Structural and Interpretive Principles:

- The structure of matter and the Universe is fractal: wave formations can be nested, exhibiting self-similar patterns at different scales.

- The observed «pointness» of elementary particles is a consequence of the limitations of our perception and interaction due to the finite propagation speed of interactions and resonance conditions that lead to localisation of wave packets.

- There is a unity of energy, its wave form and the process of perception. Everything we observe is a manifestation of the unified wave nature of energy. The differences between matter, field and interaction are due to the configuration, scale and frequency of standing waves. Observation is interpreted as active participation in a process of resonant alignment where the form of the object and the act of perception are mutually conditioned.

- Features of Electromagnetic Waves:

- Electromagnetic waves have not only a transverse but also a longitudinal component, arising due to the finiteness of their propagation speed and the need for redistribution of energy in space. This longitudinal component plays an essential role in the formation of the structure of matter.

3. logical implications of the model

Proceeding from the formulated postulates regarding the primacy of energy, the wave nature of matter, the resonant character of interactions, Euclidean space, and fractality (as outlined in the Postulates section, e.g.,), a number of logical consequences emerge. These consequences form the conceptual basis for explaining fundamental physical phenomena and the properties of matter within the framework of the proposed model.

3.1 Consequences Pertaining to the Nature of Matter and its Fundamental Properties:

- Structure and Scale of Matter: Matter, being comprised of stable standing wave formations within an energy-saturated medium (as per Postulate 2.1), derives its spatial characteristics (particle sizes, distances, boundaries) directly from the parameters of these waves. Thus, the geometry of objects is not an external attribute but is intrinsically inherent to their wave structure.

- The Nature of Mass: Mass is interpreted not as an initially inherent property but as a manifestation of a stable wave process – specifically, as a characteristic linked to the amplitude of a longitudinal standing wave and the structure of its semi-waves (as per Postulates 2.3 and 2.3.1). An increase in the amplitude or complexity of the wave structure corresponds to an increase in mass.

- The Origin of Electric Charge: Electric charge arises as a specific characteristic of standing waves with an even number of nodes. It is associated with the invariant geometrical work performed by space in the formation of a particle’s boundary semi-wave. The constancy of this work for all elementary wave units, conditioned by resonant coupling in a unified space, explains the quantisation and invariability of the elementary charge.

3.2 Consequences Pertaining to Fundamental Interactions:

- Universal Mechanism of Interactions via Resonance: All fundamental forces – electromagnetic, weak, strong, and gravitational – are various manifestations of a single principle: the resonant exchange of energy between wave structures within an energetic medium (as per Postulates 3.1 and 3.2).

- The Nature of Gravitation: Gravitation in this model is not linked to the curvature of Euclidean space (as per Postulates 4.1 and 4.2) but arises as a reaction of the energetic medium of space to a local perturbation of energy density caused by the formation of mass (a standing wave).

3.3 Consequences Pertaining to General Principles of Organisation and Perception:

- Fractality as a Universal Organisational Principle: The postulate concerning the fractal structure of matter (as per Postulate 5.1) leads to the conclusion of self-similarity in wave formations at various scales. This implies that the regularities governing elementary particles may be reflected in the structure and dynamics of cosmological objects, such as galaxies, representing different levels of a unified fractal organisation.

- Invariance of Work and Conservation of Energy: The stability of material structures (standing waves) corresponds to states wherein the invariance of geometrical work is maintained amidst changes in configuration (e.g., the number of nodes). This principle, founded upon resonance, ensures the adherence to the law of conservation of energy in wave interactions.

- The Nature of Time: Time, in accordance with Postulate 4.3, is not an independent entity but is interpreted as our perceived manifestation of the sequence of changes in wave configurations and energetic states within space.

- Energy as a Universal State Parameter: Energy (as per Postulate 1.1) determines not only the possibility of motion or thermal state but also the very possibility of a structure’s existence, its form, mass, and capacity for interaction. Changes in energy determine the phase transitions and transformations of matter.

3.4 Consequences Pertaining to Dynamic Processes:

- Absorption and Emission of Energy: The processes of absorption and emission (e.g., the emission of a photon) are not regarded as the creation or annihilation of particles from nothing, but as a reconfiguration of the resonant states of wave structures. This involves a change in wave configuration, harmonised with the overall resonance of the system and the medium.

4. Reconciliation of theoretical calculations with observed values

To test the hypothesis, calculations of key parameters of elementary particles (neutrino, electron, neutron, proton) based on the wave model have been performed. The results were compared with experimentally measured values:

| n | name | λ₀ (m) | M₀ (кг) | m₀ (kg) | d₀ (m) | λ₀ exp (m) | m₀exp (kg) | d₀exp (m) |

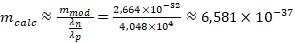

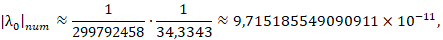

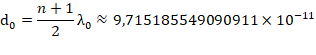

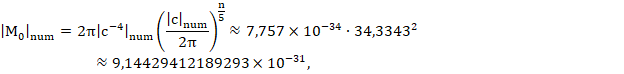

| 1 | neutrino | 9,715×10⁻¹¹ | 2,663×10⁻³² | 6,581×10⁻³⁷ | 9,715×10⁻¹¹ | 10⁻⁶ | <2.2×10⁻³⁷ | 10⁻¹⁰ |

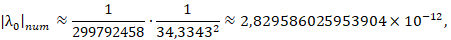

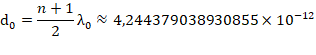

| 2 | electron | 2,83×10⁻¹² | 9,149×10⁻³¹ | 9,149×10⁻³¹ | 4,244×10⁻¹² | 2.43×10⁻¹² | 9.109×10⁻³¹ | 10⁻¹⁸ |

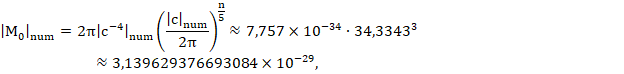

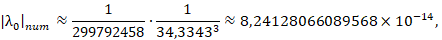

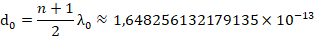

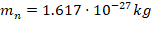

| 3 | neutron | 8,241×10⁻¹⁴ | 3,142×10⁻²⁹ | 1,617×10⁻²⁷ | 1,648×10⁻¹³ | 10⁻¹⁵ | 1.675×10⁻²⁷ | 10⁻¹⁵ |

| 4 | proton | 2,4×10⁻¹⁵ | 1,078×10⁻²⁷ | 1,617×10⁻²⁷ | 6,001×10⁻¹⁵ | 1.32×10⁻¹⁵ | 1.673×10⁻²⁷ | 10⁻¹⁵ |

Notes:

- λ₀ is the characteristic wavelength from the model;

- M₀ is the amplitude of the wave;

- m₀ — resultant mass, depends on the amplitude of the wave and the number of half-waves associated with the centre point of the wave structure;

- d₀ is the calculated diameter (or radius) of the wave structure;

- «exp» — experimental values.

Elementary charge obtained in the model:

q₀ = 1.5506912… × 10⁻¹⁹ Cl,

which is comparable with the experimental value

e = 1.602176634 × 10⁻¹⁹ Cl — the error is less than 3.2%.

The obtained values of mass, wavelength, and radius agree well with the experimental ones, especially for the electron and proton. This confirms that standing waves in the medium can be the basis for the formation of stable particles and their properties.

The obtained value of the elementary charge is also close to the experimental one, which indicates the possibility of describing the electromagnetic interaction through the internal structure of the wave object.

5. Areas Where the Model Offers a More Holistic or Physically Intuitive Explanation:

The proposed wave model of matter and fractal structure of the Universe, based on the postulates outlined above, allows for new or more intuitive physical interpretations of a number of fundamental phenomena and concepts.

- Origin of Fundamental Interactions

In this model, all fundamental forces – gravitational, electromagnetic, strong, and weak – are interpreted not as initially distinct entities, but as different manifestations of a single universal mechanism: the resonant exchange of energy between wave structures within an energy-saturated medium. This follows directly from Postulate 3.2, which states that fundamental forces are macroscopic manifestations of resonant interactions, and Postulate 3.1, which posits resonance itself as the basis of all interactions.

- Explanation of the Nature of Mass

Mass, in this model, is not a primary, postulated property but is derived as a result of a stable wave process – specifically, as a characteristic linked to the amplitude of the longitudinal component of a standing wave and the structure of its semi-waves (in accordance with Postulate 2.3). The model also explains potential «mass jitter» in strong fields as a result of internal resonant transitions within the wave structure. The change in the effective value of mass in regions of altered energy density (as per Postulate 1.2) also finds its explanation, as mass is a consequence of the amplitude of energy oscillations (as per Postulate 1.1).

- Explanation of the Nature of Electric Charge

Electric charge is associated with the specific structure of standing waves, namely those that possess an even number of nodes. Its origin is interpreted as the result of invariant geometrical work performed by space (the energetic medium, according to Postulate 1.2) during the formation of a particle’s boundary semi-wave. This approach to charge as a derivative characteristic of a wave structure (as per Postulate 2.3) allows for an explanation of its quantisation and constancy.

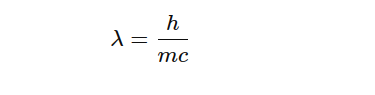

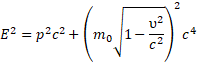

- Explanation of the Photon’s Zero Rest Mass

The photon, in this model, is considered a wave structure with an asymmetric spherical form, distinguishing it from the standing waves that constitute massive particles. This asymmetry and the absence of a closed standing wave structure capable of retaining energy at rest in a manner analogous to particles with mass explain its zero rest mass and constant motion at the speed of light, which is a consequence of its specific wave configuration (in accordance with Postulate 2.3 concerning properties determined by wave geometry).

- Explanation of the Constancy of the Speed of Light

The limiting speed of interaction propagation (c) is explained not by the properties of an abstract ‘void’, but by the fact that stable resonance (as per Postulate 3.1) in an energetic medium (as per Postulate 1.2) is possible only at a certain fundamental frequency. This frequency determines the coherent exchange of energy and sets the ultimate speed of interaction (as per Postulate 3.3). The medium itself and its properties thus arise as a manifestation of this fundamental resonance.

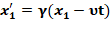

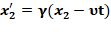

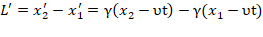

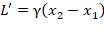

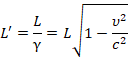

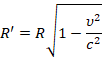

- Origin of the Lorentz Transformations

The Lorentz transformations are derived in this model not as an initial postulate, but as a consequence of the wave nature of matter (as per Postulate 2.1) and the constancy of the speed of interactions, conditioned by the fundamental resonance of the medium (as per Postulate 3.3). Length contraction and time dilation for moving objects are interpreted as real changes in their wave structures.

- Wave Nature of Particles and Wave-Particle Duality

The standing wave model naturally explains wave-particle duality. A particle interacts locally (as a ‘point’) in the region of its nodes or maximum energy density, but its distribution in space and its behaviour in certain experiments (e.g., diffraction) are determined by its wave structure (as per Postulate 2.1). ‘Point-like’ behaviour, in this context, is a consequence of limited perception and interaction conditions (as per Postulate 5.2).

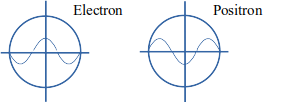

- Polarisation and Spin

These particle properties also find an explanation within the wave model. Polarisation is linked to the shape and orientation of the particle’s wave envelope. Spin can be interpreted either as a result of the distortion of the wave structure’s form relative to an ideal spherical shape (for charged particles) or as a manifestation of the internal rotation of energy density (for neutral particles with an odd number of nodes). Both aspects are characteristics of the geometry and dynamics of the wave structure (as per Postulate 2.3).

- Neutron Half-Life and Quantum Entanglement

The model proposes that neutral particles with an odd number of nodes (such as the neutron) are born in pairs with their antiparticles and are characterised by an internal rotation of energy, which leads to their quantum entanglement. The instability of the free neutron and its half-life are linked to this entangled state and its interaction with the surrounding energetic medium. It is suggested that the half-life may vary depending on the local concentration of matter (density of the energetic medium, according to Postulate 1.2), which influences the resonance conditions (as per Postulate 3.1).

- Dark Matter and Dark Energy

Observed effects attributed to dark matter and dark energy are interpreted in this model as manifestations of resonant interactions and density deformations of the energetic medium at larger, cosmological scales. This is a direct consequence of the Postulate of Fractality (Postulate 5.1), according to which galaxies can represent standing waves of energy at the corresponding fractal level.

- The Lamb Shift

This subtle effect in atomic spectra is explained as the result of the interaction of an electron (a wave structure, as per Postulate 2.1) with a local distortion of the energy density of space (as per Postulate 1.2), caused by the presence of a proton (a massive wave structure, as per Postulate 2.4). The closer the electron orbital is to the nucleus, the stronger this interaction, which leads to the shift in the energy level.

- Quantum Entanglement («Spooky Action at a Distance»)

Entanglement is interpreted as the coherent tuning of resonant systems (as per Postulate 3.1) within a unified energetic medium. For systems with internal energy rotation (such as neutral particles), the interaction can be directed ‘to a point’ (the centre of rotation), where the concept of distance in Euclidean space (as per Postulate 4.2) loses its usual meaning for this type of connection, thereby ensuring apparent instantaneity.

- Processes Beyond the Event Horizon of Black Holes

The event horizon is regarded as a boundary beyond which the energetic medium (as per Postulate 1.2) transitions into a state with a substantially different (increased) speed of interaction propagation (Postulate 3.3 allows for different speeds at different fractal levels). This may correspond to a transition to another fractal level (as per Postulate 5.1), where its own ‘Universe’ exists, perceived by us as a point or singularity.

- Reducibility of Classical and Quantum Physics

The wave model of matter (as per Postulate 2.1) inherently bridges the rigid gap between field continuity and particle discreteness. Particles are discrete, stable wave structures (quantum objects), but their interactions and propagation in the medium obey wave laws, which at the macroscopic level can lead to classical behaviour.

6. Model predictions

The proposed wave model of matter and fractal structure of the Universe allows for the formulation of a number of testable predictions, which can either confirm its main tenets or indicate the need for further refinements.

6.1. Fractal Correspondence of Scales: From Elementary Particles to Galaxies

- Essence of the Prediction: If the structure of the world is indeed fractal, as postulated in the model (Postulate 5.1), then analogies and scalable correspondences should be observed between objects at different levels of matter organisation. In particular, elementary particles, considered as standing waves of energy, may have structural and dynamic analogues on cosmological scales, for example, in the form of galaxies.

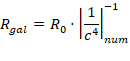

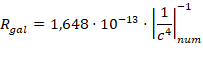

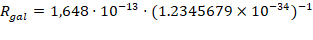

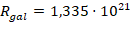

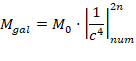

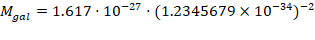

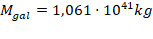

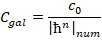

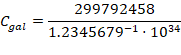

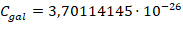

- Verification and Current Status: Appendix 8 («Scaling between the Neutron and the Milky Way») presents a calculation demonstrating that when scaling the parameters of a neutron (using fractal relationships derived in the model) to cosmological sizes, the obtained values for mass and size are close to the observed parameters of the Milky Way galaxy. The coincidence of several parameters simultaneously indicates that such a correspondence is non-random and can be considered indirect confirmation of the fractal principle. Further research could be directed towards finding similar correspondences for other types of particles and galaxies.

6.2. Influence of External Conditions on the Properties of Quantumly Entangled Particle Pairs (using the neutron and antineutron as an example)

- Essence of the Prediction: The model suggests that neutral particles with an odd number of nodes, such as the neutron, are born in pairs with their antiparticles (e.g., a neutron and an antineutron) and exist in a state of quantum entanglement, conditioned by their common wave nature and the conservation of characteristics (e.g., opposite directions of internal energy rotation). This entanglement means that the state of one particle is inextricably linked to the state of the other, irrespective of the distance between them. It is predicted that a targeted influence on one particle of such an entangled pair should lead to an instantaneous change in the measurable characteristics of the second particle.

- Experimental Verification:

- It is necessary to develop a methodology that allows for the registration of neutron-antineutron pairs directly at the moment of their creation (e.g., in annihilation reactions or high-energy collisions) and to maintain them in isolated conditions, minimising external interactions.

- Subsequently, a controlled influence (e.g., a magnetic field, a change in the density of the surrounding energetic medium) should be applied to one of the particles in the pair.

- Simultaneously, precise measurements of the characteristics of the second particle must be conducted (e.g., its lifetime before decay, interaction parameters if it is stable under the given conditions, or characteristics of its own internal energy rotation, if measurable).

- The detection of correlated changes in the second particle, synchronous with the influence on the first, would serve as confirmation of the predicted quantum entanglement and the mechanism of its influence on particle properties. The initial hypothesis regarding the dependence of the free neutron’s half-life on the density of the surrounding matter is a specific instance of this more general prediction, where the surrounding environment exerts an uncontrolled ‘influence’ on one of the components of the entangled system.

6.3. Dependence of the Fine-Structure Constant (α) on the Local Gravitational Potential

- Essence of the Prediction: The model posits that the fine-structure constant α is not a universal constant but may depend on the local energy density of space, which, in turn, is determined by the gravitational field of surrounding macro-objects. Thus, α could act as a «context-dependent» quantity.

- Experimental Verification: An experiment is proposed (described in section 7.6.4) to measure the electrostatic interaction force between two charged bodies whilst varying gravitational conditions (e.g., at different altitudes above sea level). A change in the equilibrium distance between the bodies (all other conditions being equal) could indicate a change in the effective charge and, consequently, a variability in α. The detection of statistically significant deviations would provide indirect confirmation of this hypothesis and of the influence of gravitation on electromagnetic interactions via α.

6.4. Resonant Frequencies of Macro-Objects and their Practical Application (using the Earth as an example)

- Essence of the Prediction/Consequence: This model allows for the calculation of a set of characteristic resonant frequencies for macro-objects, such as the Earth, based on their dimensions and the wave parameters derived in the theory. These frequencies correspond to different types of wave interactions (analogous to elementary particles with a varying number of nodes, n) with the given macro-object.

- Potential Applications:

- Wireless Energy Transmission: Influencing a macro-object (e.g., the Earth) at one of its resonant frequencies, or multiples thereof, could allow for the transmission of energy over considerable distances without wires, using the medium itself (the Earth as a waveguide or resonator) to convey oscillations. This resonates with the ideas of Nikola Tesla.

- Modification of Gravitational Interaction: If gravitation, according to this model, is a result of wave processes and resonance, then targeted influence at the resonant frequencies of a macro-object could theoretically lead to a local alteration of gravitational interaction.

- Detection and Generation of Gravitational Waves/Seismic Activity: The model predicts that at certain frequencies (particularly for n>4), the interaction energy transitions into internal oscillations of the macro-object, which may manifest as seismic activity or the generation of gravitational waves. Monitoring emissions at these frequencies could serve to predict or detect such activity.

7. Mathematical model of the structure of elementary particles in space

Introduction

In this chapter, a mathematical apparatus is constructed, according to which elementary particles can be described through standing waves with different number of nodes. This allows us to relate their properties to scaling in space and interaction through wave resonance between fractal levels

To understand and justify what an elementary particle in space is, the paper devotes Appendices 1, 2 and 3. Appendix 6 states the principle of scalability (fractality) in space at finite propagation speed of interactions.

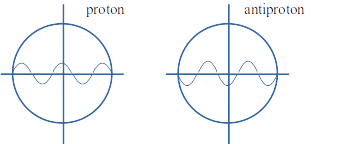

Under elementary particles in this paper we consider only four known, stable particles — neutrino, electron, neutron and proton, as well as their anti-analogues. It is assumed that only four stable stable standing waves in space can exist.

Despite the fact that the free neutron is not stable, within the framework of this model it is considered as a standing wave, under certain conditions preserving its integrity. Its half-life can be explained by its peculiarity of energy rotation within its structure, which leads to entanglement in the birth of neutron and antineutron. Since it is subject to frequent interactions due to its sufficient mass, a change in the state of one of the pair leads to a change in the state of the other.

It is assumed that the rule should be preserved — the smaller the wavelength, the higher the mass value. The larger the number of nodes, the smaller the wavelength, since we have a limited speed of propagation of interactions, the correspondingly higher the mass. This is an analogue of energy quantisation in standing waves, as in a string: energy increases with the number of nodes, while the length shortens.

It is known from experience that of the listed particles the electron and the proton have charge. In this work they should correspond to standing waves with an even number of nodes. Proceeding from this and from the known from experiments masses of particles, it is possible to assume sequences of particles in the order of increasing number of nodes of the standing wave — neutrino, electron, neutron and proton. Here only the neutron is out of the general picture. It is considered that its mass is greater than that of the proton, which based on this paper should not be. But taking into account that it has in its structure the effect of internal rotation of energy, which, when measuring the mass, in fact, is similar to the manifestation of charge between charged particles, it can lead to a misinterpretation of the obtained result. I.e., the neutron mass obtained in the experiment may be overestimated, and the interaction of rotational energy may be added to it, which leads to an overestimated mass value.

The principle of particle formation is considered in Appendix 3. A more detailed description of these processes, as well as the principles of the emergence of existing interactions, can be found in the philosophical work “Reflections: Faith, Unbelief. Spirit and Matter”, available at https://zenodo.org/records/17216895, or via the mirrors:

https://cloud.mail.ru/public/yjPE/z6MZHqH5F http://dzen.ru/a/ZoLSeRy9DQ8jA_Z2.

7.1 Relationship between dimensions and weight

7.1.1 Initial data:

To describe an elementary particle as a wave object, let us consider the interaction of two interconnected components of the electromagnetic wave — the transverse and the longitudinal. Their interaction is examined in the cross section.

The term “longitudinal wave” is used in an extended sense: it is not a new type of wave, but rather a part of the process associated with the front and the finite “thickness” of the electromagnetic wave. In essence, it is the same field, only viewed not separately, but as an integral part of the wave itself.

- Interaction velocity: It is taken equal to c (speed of light in vacuum).

- Wave propagation: A wave is considered to have components along two conventional orthogonal axes:

- The x-axis: is responsible for the spatial dimension (longitudinal wave).

- The y-axis: is responsible for the energy/mass characteristic (energy related transverse wave).

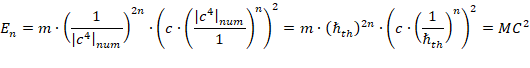

- Transverse component: This component is considered as a carrier of amplitude information related to the energy density. Through the formula E=mc² it allows to pass to the concept of mass.

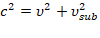

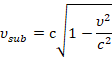

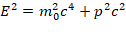

Constancy of c²: Since the interaction velocity c is a constant, the value of c² becomes important. If a wave propagates simultaneously along the x and y axes with velocity components υₓ and υy respectively, then by Pythagoras’ theorem:

This relationship reflects the balance between the geometric (size) and energetic (mass) manifestations of the wave.

(Note: In this section, to simplify mathematical expressions and focus on numerical relationships, we will often omit physical dimensions by using numerical values of quantities. For example, c may refer to its numerical value in the SI system. Restoration of dimensions is a separate task).

7.1.2 Derivation of size and mass limits for standing waves

In order to form a stable standing wave, it is necessary that all its parts remain in interaction. This imposes restrictions on the maximum and minimum sizes of such wave formations and their associated masses.

A standing wave requires that all points of the wave can remain in interaction, i.e. the maximum distance between points must not exceed the path that the signal can travel in a given time. If we were to consider only the propagation of the wave along the x-axis, then at Δt≤ 1/c we would observe an interaction between the initial and final points of propagation. Since we consider propagation along two orthogonal directions, the interaction time limit is replaced by the condition Δt 1/≤| c²|ₙᵤₘ. which corresponds to the interaction limit when both the geometric (x) and energy (y) components are fully engaged.

In this case, we can speak about the maximum size of standing waves in the region of space, which will take place at once for both types of waves — transverse and longitudinal components. Their size cannot exceed the size:

1. Limit dimensions (L):

We consider the propagation of the interaction along two orthogonal directions (size x and energy/mass y) where the total velocity is bounded by c.

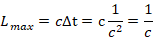

- Maximum characteristic size (Lₘₐₓ): The largest size at which the standing wave components can effectively interact will not exceed

This corresponds to the case where the bulk of the «rate of change» is directed along the spatial coordinate.

- Minimum characteristic size (Lₘᵢₙ ): If we consider a system already bounded by the size

and apply the same logic to the internal structure, the minimum size at which a standing wave can still exist as a detached structure is

Hence, standing waves (particles) must exist in a range of characteristic sizes:

2. Mass limits (M):

Mass in this model is related to the energy of the transverse (electromagnetic in nature) component of the wave propagating along the sphere. Therefore, a 2π multiplier appears in the expressions for energy and mass, taking into account the geometry of the circle/sphere.

- Energy Range (E): Similar to the dimensions, the energy will be in a range proportional to 2π/c² to 2π/c.

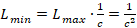

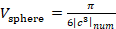

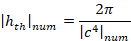

- Mass range (M): Using E=Mc² (where M is the amplitude of the longitudinal wave associated with the mass of the particle), we obtain a range for M: M(min) (_) ₙᵤₘ=(2π/c²ₙᵤₘ)/c²ₙᵤₘ=2π/c⁴ₙᵤₘ M(max) (_) ₙᵤₘ=(2π/cₙᵤₘ)/c²ₙᵤₘ=2π/c³ₙᵤₘ. Thus, the amplitude of M (mass) is in the range:

These ranges show that both size and mass are related to the speed of light in a stepwise manner. The ratio of the maximum and minimum values in each range (for L and for M) is cₙᵤₘ . This indicates that the quantisation of states inside these ranges should also follow the power law.

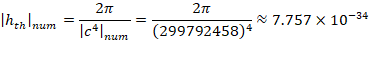

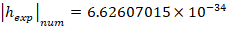

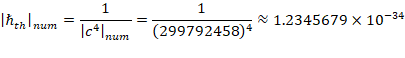

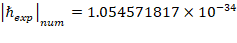

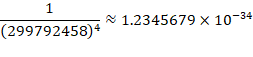

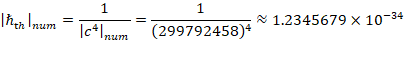

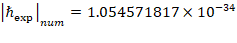

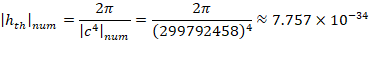

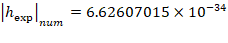

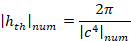

Here we see a value (constant) of 2π/c⁴, which is remarkably close to the value of Planck’s constant:

If:

Then:

The difference from the experimentally obtained value of Planck’s constant is connected with that at calculation of the total mass of a standing wave, similarly to GR, it is necessary to take into account that gravitation «feels» the integral picture of density. If in the gaps between compactifications there is a void, then instead of just summation of masses it is necessary to take into account redistribution of work (energy) in space. This will be discussed below. This imposes its imprint on the value of the experimentally obtained Planck constant.

7.1.3 Node quantisation and elementary particle parameters

1. Condition for the formation of nodes:

For the formation of stable knots of a standing wave on a circle (representing the cross section of the spherical structure of the particle), the condition of consistency of the wave components is necessary. Let us assume that knots arise at equality of projections of interaction velocities on orthogonal x and y axes: υₓ= υy.

- In polar coordinates, this condition means cosθ= sinθ, which is fulfilled at angles θ=π/4+nπ/2, where n∈ Z.

- On a complete circle (2π), this gives exactly four symmetric directions (45°, 135°, 225°, 315°) in which the formation of stable knots is possible. This leads to the assumption that no more than four basic stable standing wave types are possible, corresponding to 1, 2, 3, and 4 nodes.

Physically, this means that a standing node is formed only when the wave in its circular dynamics propagates energy uniformly along both spatial dimensions. If one of the velocity components becomes dominant (or equal to zero), either a purely translational wave (without nodes) or an unstable system incapable of stable self-consistent resonance arises.

The appearance of the fifth node breaks the equality of the velocity components, and the energy starts to go in the longitudinal direction — forming not a wave but a mass contribution.

2. Principle of degree quantisation:

Since the ranges for L and M are defined by degrees c, the division of these ranges into discrete levels (corresponding to n nodes) must also be degree-dependent. We have 4 types of stable wave states (particles). Conceptually, let us add to these 4 states a fifth «step» or «level» which, is associated with the «birth of mass» as an entity beyond the purely wave state, or with the transition to the next fractal level. Thus, the total number of conceptual «steps» or «divisions» for the full range of quantisation is accepted equal to five.

This 5-step quantisation assumption means that if we have some base multiplier K₀ , then the nth level will be characterised by the multiplier (K₀)n/5 .

3. Definition of quantum of change and formulae for mass and wavelength:

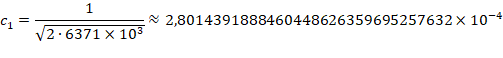

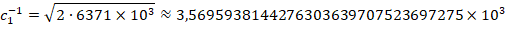

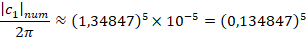

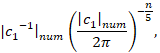

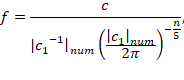

- As a basis for scaling, let us take the quantity related to the ratio of the speed of light to the characteristic angular size 2π: K₀=cₙᵤₘ/(2π).

- Then the «quantisation multiplier» for the nth state will be (K₀)(1/5)or, for n n nodes, (K₀)(n) (/5)= (cₙᵤₘ /(2π)) (n) (/5).

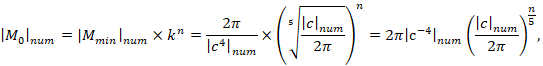

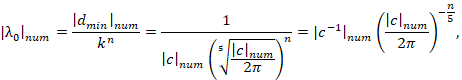

Based on the principle that the mass (M₀ ) increases from its minimum Mₘᵢₙ_ₙᵤₘ , and the characteristic wavelength (λ₀ ) decreases from its maximum characteristic value Lₘₐₓ_ₙᵤₘ 1/cₙᵤₘ= as the number of «quanta» n increases:

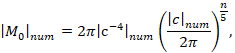

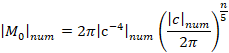

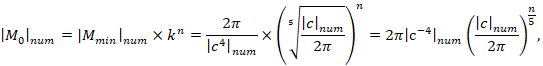

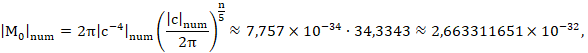

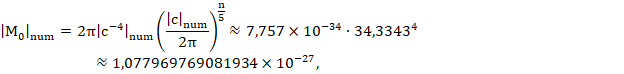

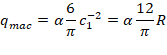

- Amplitude of the longitudinal wave (mass M₀ ):

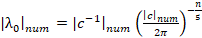

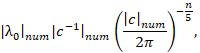

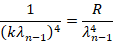

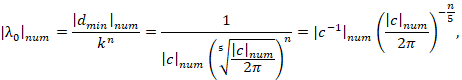

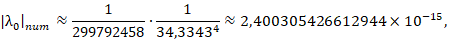

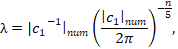

- Characteristic wavelength (λ₀ ):

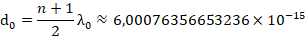

- Calculated standing wave diameter (d₀ ):

These formulas allow to relate the properties of particles (mass, size) to the number of nodes n of their wave structure, proceeding from the fundamental constant c and the principle of degree quantisation based on 5 conceptual levels.

Remark:

In this chapter, mass refers to the amplitude of a longitudinal wave. The total mass of a particle as a wave system consisting of several zones will be considered in the following chapters.

7.2 Extreme States of Wave Structures: From Photons to Limits of Energy Compression

In addition to the four primary types of stable standing waves corresponding to elementary particles with node numbers n=1,2,3,4, this model also considers limiting states characterised by n=0, n=−1, and n=5. These states do not describe stable massive particles but rather other forms of energy manifestation: electromagnetic waves, photons, and the ultimate compression of energy linked to fractal transitions.

7.2.1. States n=0 and n=−1: Photons and Electromagnetic Waves

States with n=0 and n=−1 within this model characterise electromagnetic radiation, particularly photons, and their transition to classical electromagnetic waves.

7.2.1.1. Limiting Wavelengths of the Photon

Utilising the primary formula for the characteristic wavelength

states with n=0 and n=−1 can be interpreted as follows:

- For n=0 (Minimum photon wavelength, λₘᵢₙ):

∣λ₀∣ₙᵤₘ=1/cₙᵤₘ≈3.33⋅10⁻⁹ m (where cₙᵤₘ≈3⋅10⁸). This state can be regarded as a limit where the wave structure has not yet formed a closed standing wave, characteristic of massive particles. Here, the energy is maximally concentrated in the “spatial” component of the interaction. This corresponds to short-wavelength photons (for example, hard X-rays), which exhibit the most pronounced corpuscular properties.

- For n=−1 (Maximum photon wavelength, λmax):

∣λ₀∣ₙᵤₘ=(1/cₙᵤₘ)∙(2π/cₙᵤₘ) ¹⁄⁵≈ₘ=(1/cₙᵤₘ)∙Ks, where Ks==(2π/ cₙᵤₘ) ¹⁄⁵ is your principal quantising multiplier (Ks≈34.3343). Then λₘₐₓ≈(3.33×10⁻⁹ m)⋅34.3343≈1.14⋅10⁻⁷ m. This state is considered the limit beyond which a directed energy quantum (photon) ceases to exist as a localised object and transitions into the category of classical electromagnetic waves, propagating more isotropically. The rate of ‘bulge’ formation (related to frequency) still defines a noticeable directionality of radiation here.

7.2.1.2. Mechanism of Photon Creation

A photon is created during dynamic processes involving changes in the energetic state of matter, for instance, when an electron transitions between energy levels in an atom. This transition is associated with the accelerated motion of the electron.

- The accelerated motion of a charged electron constitutes a rapid, directed change in the energy density of the surrounding medium.

- This change generates a longitudinal wave of energy density, which, in turn, gives rise to its accompanying transverse electromagnetic component.

- Due to the localized and directional nature of its formation, the emerging electromagnetic wave does not have time to form a fully closed spherical shell. Instead, a wave structure is created with an open shell elongated forward (in the direction of radiation), resembling a paraboloid. This asymmetry (“convexity”) determines the directed motion of the photon.

7.2.1.3. Properties of the Photon

- Zero Rest Mass: The absence of a closed standing wave structure capable of retaining energy in a state of rest explains the photon’s zero rest mass.

- ‘Mass Equivalent’ and Directionality: The photon carries energy and momentum. The presence of a longitudinal wave component (albeit not a standing one in the sense of a massive particle) and the asymmetric form of its wave envelope (the non-coincidence of its geometric centre and ‘energy centre’ or ‘centre of mass’) are interconnected manifestations of its dynamic mass (E/c²) and ensure its directed motion.

- Spin: The structure of the photon’s boundary (envelope) may determine its spin properties, related to symmetry (or lack thereof) in the direction of motion, as well as possible ‘twisting’ of the wave along its propagation axis.

7.2.1.4. Transition to Classical Electromagnetic Waves

As the frequency of radiation decreases (wavelength increases, i.e., for n→−1 and beyond, past the λₘₐₓ photon), the process of change in the source’s energetic state (e.g., in a radio antenna) becomes slower and more extended. The ‘bulge’ on the sphere of energy propagation becomes negligibly small compared to the overall sphere. Consequently, directionality is lost, and the radiation becomes predominantly spherical, corresponding to classical electromagnetic waves.

7.2.2. State n=5: Limit of Energy Compression and Fractal Transition

The state n=5 represents another extreme case within the model.

- Characteristics: It is proposed that at n=5, «all interaction velocity belongs to the energy domain.» This corresponds to the ultimate compression of energy.

- Size and Nature: Such a state is associated with the transition of energy into a region with a size less than |1/c²|ₙᵤₘ (the minimum size for particles with n=1..4). This region, existing within each elementary particle, is interpreted as an analogue of a black hole – a point of transition to a new, deeper level of spatial fractalisation (as per Postulate 5.1).

- Point-like Matter and Wave Functions: It is this region of ultimate energy compression (n=5) that can be considered a manifestation of ‘point-like matter’ (as per Postulate 5.2), whose behaviour within its surrounding wave field (the standing wave with n=1..4) may be described by wave functions, as is customary in quantum mechanics.

- Gravitational Waves: At n=5, the model predicts the phenomenon of energy compression and the possible emission of gravitational waves propagating in all directions. Appendix 9 also indicates that interaction with a macro-object at frequencies corresponding to n>4 can lead to energy transitioning into internal oscillations, manifesting as seismic activity or the generation of gravitational waves.

These extreme states (n=0,−1,5) extend the application of the wave model beyond the description of only stable massive particles, allowing for a qualitative interpretation of the nature of photons, electromagnetic waves, and possible mechanisms for fractal transitions at the sub-particle level.

Okay, here is the British English translation of the revised section 7.2.3, incorporating your points about the bullet-like shape and the offset centres of mass for gamma radiation:

7.2.3. High-Energy Quanta from Nuclear Interactions (Gamma Radiation)

A distinct type of high-energy electromagnetic radiation – gamma quanta – finds its explanation within this model not only through annihilation or the decay of elementary particles but also through more profound processes linked to the structural rearrangement of nucleons (protons and neutrons) themselves.

If nucleons are considered complex standing waves composed of several ‘semi-waves’ (as discussed in the context of their possible five-quark structure and the relation of charge to the work of a semi-wave), then during their intense interactions or rearrangements (e.g., in nuclear reactions), it is possible for individual such energetic fragments – ‘semi-wave shards’ – to be liberated.

These fragments are characterised by the following properties:

- They carry a significant portion of energy, determined by the invariant work associated with the formation of a semi-wave within the nucleon’s structure.

- Their characteristic dimensions (wavelengths) are commensurate with the sizes of nucleons (of the order of 10⁻¹⁵…10⁻¹⁶ m), which corresponds to their high energy (E=hc/λ).

- It is proposed that these ‘shards’, being dynamically liberated, acquire an asymmetric, elongated form, akin to a bullet. Such a formation leads to a non-coincidence of the geometric centre of this wave structure and its effective energy centre (or ‘physical centre of mass’). It is precisely this asymmetry and the uncompensated internal structure that compel this wave packet to move at the speed of light.

- Although such a fragment may represent a ‘closed’ portion of energy (e.g., one or several semi-waves from the original nucleon structure), it does not constitute a stable standing wave capable of existing at rest like a massive particle (i.e., it does not meet the conditions for n=1..4). Therefore, its energy must be radiated in the form of a moving gamma quantum.

Thus, gamma radiation is distinguished from photons in the optical or X-ray range (arising from electron transitions) not only by its considerably higher energy but also by the specific mechanism of its creation, being linked to the liberation and rearrangement of energetic sub-structures at the nucleon level. Their ‘bullet-like’ form and the resultant offset of centres explain their directed motion and corpuscular properties whilst retaining their wave nature.

7.3 Features of Elementary Particles in the Wave Model

In accordance with this model, the four primary stable types of elementary particles (neutrino, electron, neutron, and proton) represent standing waves with node numbers n=1,2,3, and 4 respectively. Each value of n defines unique geometrical and dynamic characteristics of the wave structure, which manifest as the specific properties of the particle.

7.3.1. Neutrino (n=1)

- Structure and Size: At n=1, a standing wave with a single node is formed. According to the formulae (from section 7.1.3), this state is characterised by the largest characteristic wavelength (λ₀) and, consequently, the largest calculated diameter (d₀) amongst the particles considered, commensurate with the size of an atom.

- Mass: It possesses the minimum wave amplitude (M₀) and, as a result, the minimum mass.

- Interaction: Its large size and minimal mass render the neutrino a particle with very weak interaction with other matter.

- Internal Energy Rotation: The model posits that neutrino formation occurs when a portion of energy from the ‘spatial dimension’ is added to the ‘electromagnetic wave dimension’ (the transverse component propagating on a sphere). As the transverse EM wave is spherical in nature, this leads to the emergence of internal energy rotation within the neutrino’s structure. This distinguishes particles with an odd n (neutrino, neutron).

- Charge: The absence of charge is explained by the odd number of nodes and the presence of internal energy rotation, rather than a stationary boundary structure necessary for charge manifestation.

7.3.2. Electron (n=2)

- Structure and Charge: At n=2 (an even number of nodes), the particle receives a second portion of energy from the spatial side, which, according to the model, eliminates the internal energy rotation (characteristic of n=1) and leads to the appearance of electric charge.

- Nature of Charge: Charge is interpreted as the work performed by space (the energetic medium) to create one boundary semi-wave of the standing wave. The constancy of this work for all elementary wave units accounts for the quantisation and invariability of the elementary charge.

- Mass and Size: The wavelength λ₀ and diameter d₀ for the electron are smaller than those for the neutrino, whilst the amplitude M0 (and, consequently, mass) is larger, according to the formulae in section 7.1.3.

7.3.3. Neutron (n=3)

- Structure and Internal Rotation: At n=3 (an odd number of nodes), a newly acquired portion of work (energy) again disrupts the symmetry required for charge, reinstating the effect of internal energy rotation within the particle, analogously to the neutrino.

- Charge: It is an electrically neutral particle.

- Mass and Size: Compared to the electron, the neutron has a smaller λ₀ and d₀, and a larger M₀ (base amplitude/mass). However, as will be detailed in section 7.7.5, its observed mass requires additional factors to be considered. It is important to note that standard physics typically does not consider such internal energy rotation as a direct additive contribution to the rest mass of neutral particles in this manner. In this model, however, it is proposed that this rotational energy, during the neutron’s interactions (e.g., when its mass is determined via decay products or in nuclear interactions), may manifest as an additional contribution to its effective, measured mass. This is analogous to how, if the observed electrostatic interaction force between charged particles were mistakenly interpreted not as a manifestation of their charges but as an additional contribution to their individual masses, it would also lead to an overestimation of the latter. Thus, in your model, the ‘geometric’ mass of the neutron, determined solely by the standing wave amplitude M₀ for n=3, might be lower than that of the proton (n=4), but its experimentally determined mass appears higher precisely due to this (unaccounted for in standard models, or differently interpreted) contribution from internal energy rotation.

- Quantum Entanglement: Like other particles with an odd n and internal energy rotation, neutrons (when pair-produced with antineutrons) exist in a state of quantum entanglement. This property, as previously discussed, can influence their stability and decay characteristics.

7.3.4. Proton (n=4)

- Structure and Charge: At n=4 (an even number of nodes), the situation is analogous to the electron: the structure again becomes such that internal energy rotation is absent, and the particle exhibits electric charge.

- Sign of Charge: The model posits that for the proton, the sign of the charge will be opposite to that of the electron’s charge. This is related to the different configuration or “orientation” of space in forming the boundary half-wave for n=2 and n=4.

- Mass and Size: The proton possesses the smallest λ₀ and d₀, and the largest M₀ (mass) among the four particles considered.

7.3.5. General Principle: Energy Rotation or Charge

The model leads to the conclusion that for the principal stable particles, there is a form of alternative: «either we have internal energy rotation (for odd n), or charge (for even n).» This reflects two distinct ways in which a particle’s wave structure can interact with the surrounding energetic medium or manifest its internal dynamics.

7.3.6. Pair Production of Particles

It is important to note that, in accordance with the law of conservation of energy, the creation of particles (as wave structures from the energy of the medium) should occur in pairs (particle-antiparticle). For neutral particles, such as neutron-antineutron or neutrino-antineutrino, the distinction within a pair may lie in the opposing directions of internal energy rotation, which conditions their quantum entanglement.

This description of the features of elementary particles arises from their representation as standing waves with varying numbers of nodes, which determines their key physical characteristics within the proposed theory.

7.4 The Nature of Elementary Particles in the Wave Model

The representation of elementary particles as standing waves not only allows for the calculation of their parameters but also offers intuitive images of their structure and interactions, explaining their key properties.

7.4.1. Idealised Model: Spherical Wave with Internal Structure

In its simplest, idealised representation, an elementary particle (a standing wave, as per Postulate 2.1) can be likened to a spherical object. Within this sphere, regions of increased and decreased energy density alternate, forming an internal structure of semi-waves. This picture resembles a resilient ball undergoing complex volumetric oscillations.

- For neutral particles (with an odd n, such as neutrinos and neutrons), in addition to the radial distribution of energy density, the presence of internal rotation or ‘torsion’ of energy density along a certain axis is characteristic. This is a consequence of their specific wave configuration, as discussed in section 7.3.

7.4.2. The Real Particle: Interaction with the Medium, Spin, and Forces

In practice, the ideal spherical form of a particle is inevitably distorted.

- The process of particle creation (as a wave formation from the energy of the medium) is accompanied by changes in energy density in the surrounding space.

- As a particle has a finite size, its boundary is acted upon by forces of varying magnitude and direction from the energetic medium (as per Postulate 1.2), which leads to the distortion of its wave envelope.

- It is precisely this dynamic curvature and asymmetry of the particle’s real wave structure, arising from its interaction with the medium, that this model proposes to consider as a possible mechanism for the emergence of spin. Spin, therefore, is not an inherently abstract property, but rather reflects the geometry and dynamics of a real wave object.

- The asymmetry of form and energy distribution also leads to the emergence of interaction forces between particles.

7.4.3. Manifestation of the Work of Space: Charge and Internal Rotation

A fundamental principle, following from the unity of space and the resonant character of all interactions (as per Postulates 1.2 and 3.1), is the invariance of the work performed by space (the energetic medium) in forming each semi-wave of a particle’s standing wave. This work manifests differently for charged and neutral particles:

- Charged particles (n is even, such as electrons and protons): The work of space is realised in the formation of a stable gradient of energy density at the particle’s boundary – either an increased or decreased density compared to the medium. This gradient is the manifestation of electric charge. The charge is related to the work expended in creating one boundary semi-wave. The constancy (quantisation) of the elementary charge is a direct consequence of the invariance of this work.

- Neutral particles (n is odd, such as neutrinos and neutrons): For these particles, the work of space manifests not as an external density gradient but as the organisation of internal energy rotation (or ‘torsion’ of energy density). This is also a characteristic of the work expended by space to maintain their specific wave structure.

7.4.4. Particle Mass: A Dynamic Characteristic and the Influence of Internal Rotation

- Mass as Amplitude: In this model, the mass M₀ of a particle (as per Postulate 2.3.1) is directly related to the amplitude of its longitudinal standing wave.

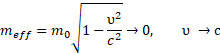

- Conservation of Work during Motion: When the velocity of a particle changes, its wave structure (size, wavelength λ₀) alters. For the invariant work (W=M₀λ₀/π) per semi-wave to be conserved, the amplitude M₀ (i.e., mass) must also change. This explains the relativistic change in mass with changes in velocity and size.

- Influence of Internal Rotation on the Measured Mass of Neutral Particles: The energy of internal rotation, inherent to neutral particles (neutrinos, neutrons), contributes significantly to their measured mass. Standard methods of mass determination… record the total energy of the particle without distinguishing between the contribution from the ‘pure’ amplitude of the standing wave and the contribution from the energy of its internal rotation.

- This ‘additional’ manifestation of rotational energy can be complex. Analogous to a magnetic dipole, the internal rotation of energy may create a form of ‘poles’. When interacting with charged particles or external fields, it might manifest uniformly (e.g., as an effective attraction, adding to the gravitational one). However, when two such neutral particles interact with each other, their ‘rotational moments’ could interact in a manner similar to magnets, leading to both attraction and repulsion depending on their mutual orientation.

- In experiments determining mass, where various orientations and types of interactions are averaged, this rotational effect may yield an averaged, ‘uniform’ contribution to the measured effective mass.

- Whilst the effects of charge are accounted for when determining the mass of charged particles… a similar consideration for the ‘energy of rotation’ in neutral particles is not standardly made.

- It is precisely this unaccounted for (or differently interpreted) contribution from internal energy rotation, that leads to the experimentally measured mass of the neutron being higher than might be expected from a simple comparison of node numbers (n=3 for the neutron versus n=4 for the proton), if only the ‘geometric’ mass from the standing wave amplitude were considered. This explains the necessity of introducing correction factors when calculating the masses of neutral particles within this model (see section 7.7.5).

Thus, elementary particles in this model are presented as complex, dynamic wave structures, whose observable properties (mass, charge, spin) are manifestations of their geometry, internal energy dynamics, and interaction with the surrounding energetic medium.

7.5 Interference of Standing Waves (Particles)

7.5.1. Principles of Interaction of Standing Waves (Particles) in this Model

As previously established, elementary particles in this model represent stable standing waves (as per Postulate 2.1), whose internal structure is formed in such a way as to maximally utilise the available interaction speed (c) within the energetic medium (as per Postulate 1.2). This implies that each particle is a densely packed, resonant wave formation.

Direct ‘penetration’ of one such standing wave (particle) into another without disrupting their internal structures appears impossible. This is corroborated by experimental observations, for example, in nuclear reactions, where significant energies, leading to a complete rearrangement of their wave structures, are required for the fusion or fission of particles.

Instead of mechanical penetration, interaction between particles in this model occurs through an exchange of energy, conditioned by the ‘work of space’. The ‘work of space’ is understood as the energy expended or released by the energetic medium during the formation or alteration of the particles’ wave structures (see section 7.6 concerning the nature of charge). The system strives to minimise the overall energetic stress (or total work of space):

- Oppositely charged particles attract because their combined field formation requires less total work of space compared to their separate existence.

- Like-charged particles repel because their proximity increases the overall stress and necessitates greater work of space.

- Uncharged rotating particles (e.g., neutrons) may also exhibit mutual attraction (strong interaction at short distances) due to the interaction of their ‘energetic moments’ or fields created by the internal rotation of energy, which is also linked to the minimisation of the work of space in a specific configuration.

These mechanisms describe the direct force interactions of particles. The phenomenon of interference, however, arises under different conditions, when these direct interactions are weakened, and other aspects of the wave nature of particles and their interaction with the medium come to the fore.

7.5.2. Conditions for the Emergence of Interference: Weakening of Direct Interaction

Interference is typically observed when particles pass through narrow slits, diffraction gratings, or are reflected from thin films. In such situations, direct ‘force’ interaction between particles (if their flux is sufficiently rarefied) or between a particle and the massive parts of the experimental setup (excluding the edges of obstacles) is minimised.

- The Single-Slit Experiment as an Example: When a particle (wave) passes through a single slit, it interacts predominantly with the edges of this slit. If the slit is sufficiently narrow (commensurate with the particle’s wavelength), its wave structure undergoes diffractive distortion. In this model, this can be interpreted as the ‘work of space’ at the slit edges altering the configuration of the passing wave. In this state, the wave is no longer entirely a standing wave in the sense of a free particle but is rather a perturbation propagating with minimal ‘resistance’ from the medium after traversing the slit.

In simplified terms, this can be represented as follows: if a particle is a standing wave, then when passing through a narrow slit its structure “adjusts” to the boundaries, similar to how a person squeezing through too narrow a doorway is forced to alter their movement. As a result, the trajectory and the final distribution on the screen depend on how the particle initially entered the slit, which leads to the probabilistic pattern of the observed outcomes.

7.5.3. Interference as a Resonance of the Wave Structure with the Medium Modulated by Obstacles

The classical explanation of interference (e.g., in Young’s double-slit experiment) is based on the principle of wave superposition. Within this model, this phenomenon can be further elucidated by considering it as the result of a resonant interaction of each individual particle’s wave structure with the energetic medium, whose properties are locally modulated by the presence of obstacles (slits).

- Slits as Modulators of the Medium: Two (or more) slits create specific boundary conditions for the ‘work of space’ and the propagation of wave disturbances in the medium. They act as secondary coherent sources or as channels through which the particle’s wave structure can pass, undergoing certain phase changes.

- Resonant Propagation: Each particle (wave), upon passing through the system of slits, interacts with this modulated medium. Its subsequent propagation is not arbitrary but is directed along trajectories corresponding to constructive resonance with its own wave structure and the structure of the medium as altered by the slits. That is, the particle predominantly arrives in those regions of the screen where the conditions for its wave propagation (considering the phase shifts introduced by the slits) are resonantly ‘permitted’ or energetically favourable.

- Formation of the Interference Pattern: The totality of such resonant trajectories for a multitude of particles forms the observed interference pattern of alternating maxima and minima.

7.5.4. Connection with the Wave Function and Probabilistic Description in Quantum Mechanics

It should be noted that standard quantum mechanics describes the interference of single particles through the wave function, the squared modulus of which determines the probability of detecting a particle at a given point. This approach is an exceptionally effective mathematical tool, allowing the description of extended wave-like objects to be reduced to the representation of point-like particles. However, in the proposed model, the emphasis is shifted toward the physical interpretation of the wave structure itself, where probabilistic distributions are linked to the resonance conditions of its interaction with the medium. In this model, this probabilistic description may receive the following interpretation:

- The wave function in quantum mechanics can be regarded as a mathematical tool effectively describing the resultant distribution of possible resonant paths for the particle-wave under the given experimental conditions.

- Regions of high probability (interference maxima) correspond to zones where conditions for constructive resonance of the particle’s wave structure with the medium (modulated by the slits) are most favourable.

- Regions of low probability (minima) are zones where resonant conditions are not met or lead to destructive superposition of wave components.

Thus, interference in this model is not merely an abstract superposition of waves but a consequence of specific resonant conditions arising from the interaction of a particle’s wave structure with an energetic medium whose properties are altered by the presence of obstacles. This approach aims to provide a more physical picture of the phenomenon, without contradicting the successful mathematical apparatus of quantum mechanics.

7.6 Work as the Basis of Charge: A Geometrical Interpretation

In the preceding sections, it was demonstrated that elementary particles, in this model, are standing waves in space (as per Postulate 2.1), formed under the influence of the energy of the medium (as per Postulates 1.1 and 1.2). Space (the energetic medium) performs work in creating an oscillatory structure – a standing wave with a specific number of nodes. This work, in each elementary portion of the wave, is expressed in the form of a semi-wave. The question arises: what is the precise physical meaning of the work performed in this process, and how does it relate to a fundamental characteristic of a particle – its electric charge?

7.6.1. The Geometrical Nature of the Invariant Work of a Semi-Wave

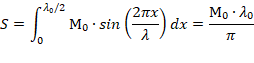

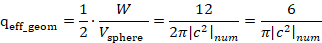

Let us represent an elementary particle as a standing wave composed of n+1 semi-waves (according to section 7.1.3). Each semi-wave is a sinusoidal oscillation of energy density, arising from the energetic interaction of space with a local region. If we assume the oscillation profile to be sinusoidal, the area under one semi-wave (which in this model is interpreted as the work W performed by space to create this semi-wave) can be defined as:

where:

- M₀ is the amplitude of the wave, corresponding in our model to the ‘amplitude mass’;

- λ₀ is the characteristic wavelength (the size of one complete oscillation).

Thus, the work per semi-wave is:

Substituting into this equation the formulae for calculating the amplitude M0 and wavelength λ0 from section 7.1.3:

From the final expression, it is evident that the work W, performed by space to create one semi-wave, is an invariant quantity, independent of the number of nodes n of the standing wave. This is a key consequence of the model, as the formulae for M₀ and λ₀ were initially constructed based on the principle of conserving this work.

7.6.2. From Invariant Work to Physical Charge: The Role of Symmetry and the Fine-Structure Constant

As charge in this model is understood as a fundamental characteristic determining a particle’s interaction with an electromagnetic field, and interaction is a result of energetic work (as per Postulates 3.1 and 3.2), it is logical to associate charge with this invariant work W.

It is proposed that the boundary semi-wave of the particle is responsible for its direct electromagnetic interaction with an external field – it is this that creates effects at distances exceeding the particle’s own size. However, the work W itself characterises the energetic contribution to the structure of the semi-wave. For this work to manifest as an interaction force in external space, the scale of this manifestation must be considered.

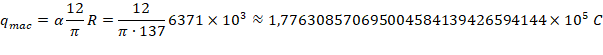

- Scale of Charge Manifestation: As noted previously, manifestations of interactions in external space commence at distances exceeding the characteristic size 1/cₙᵤₘ. Therefore, it is pertinent to consider the work W as ‘distributed’ or manifested within a volume characteristic of this scale. Such a volume can be a sphere with diameter D=1/cₙᵤₘ (radius R=1/(2cₙᵤₘ)), as discussed earlier.

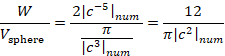

- ‘Geometrical’ Work Density (Proto-Charge): The total work density W within this volume

amounts to:

However, it should be considered that this quantity, 12/π|c²|ₙᵤₘ, characterises the total work density associated with the formation of the particle as a stable wave structure under the influence of a symmetrical, omnidirectional ‘pressure’ from the energetic medium. In this model, the particle is viewed as a local condensation of energy around a centre of mass, which is situated in the middle of the volumetric wave construct. Space acts symmetrically upon this construct from all directions to maintain it.

During the external interaction of two such particles at sufficiently large distances (e.g., in Coulomb’s law), where we can consider them as point-like centres of force, the interaction along a specific direction will be determined not by the entire spherical work of formation, but rather by its effective ‘projection’ or ‘half-contribution’ relative to the line connecting their centres of mass. One might say that, owing to the symmetry of the ‘particle-medium’ system, only the component of the ‘work of space’ pertaining to ‘half’ of the complete spherical structure, oriented in the given direction, comes into effect during an interaction along a specific direction. That is, the total work W (or its density) is distributed around the centre of mass in all directions, but in a pairwise interaction at a distance, two principal ‘directions’ of action along the line connecting them can be distinguished.

Consequently, the effective amount of work participating in external electromagnetic interaction (let us term it the ‘effective geometrical charge’, qeff_geom) participating in an external electromagnetic interaction along a specific direction will be half of the total work density calculated for the entire spherical structure:

Numerically, qeff_geom≈2.12518×10⁻¹⁷ (in arbitrary units, where cₙᵤₘ is the numerical value of the speed of light).

- Introduction of the Fine-Structure Constant (α) and Physical Charge (e): This value qeff_geom is comparable to the elementary charge e≈1.602×10⁻¹⁹ C via the fine-structure constant α≈1/137.036:

e≈qeff_geom⋅α

More precisely, qphys_calc=qeff_geom⋅α≈(2.12518×10⁻¹⁷)/137.036≈1.5508×10⁻¹⁹ (in arbitrary units of charge, if α is dimensionless). This value is close to the experimental elementary charge, as noted in section 4.

- Interpretation of α: The fine-structure constant α, in this model, acts not as a primary constant of the electromagnetic interaction strength, but as a coefficient of the efficiency of manifestation of this geometrical work in external space. It reflects what fraction of the ‘raw’ geometrical work of a semi-wave actually participates in external electromagnetic interactions. The smallness of α implies that only a minor portion of this structural work is effectively ‘radiated’ or manifested outwardly. This efficiency may depend on the properties of the energetic medium itself (its ‘permeability’ to this type of work, or ‘viscosity’), which, in turn, could be related to the local energy density and, consequently, to the gravitational potential.

- Constancy of the Elementary Charge e: This is explained by the invariance of the work W required to create a semi-wave and, under terrestrial conditions, the observed constancy of α. If α indeed depends on the gravitational potential, then under different conditions e could possess a different value (which is testable via the experiment proposed in section 7.6.4). This also explains why charge does not depend on the number of nodes (apart from the condition of evenness for its emergence) or the particle’s velocity – it reflects the fundamental act of space performing work to create a stable wave unit capable of external electromagnetic interaction.

7.6.3 On the nature of the fine structure constant

It has been shown above that the value of the elementary charge calculated from geometrical relations differs from the experimentally measured one — and this difference is a multiple of the fine structure constant. Moreover, it is important that the experimental value of the charge is smaller than the theoretical one.